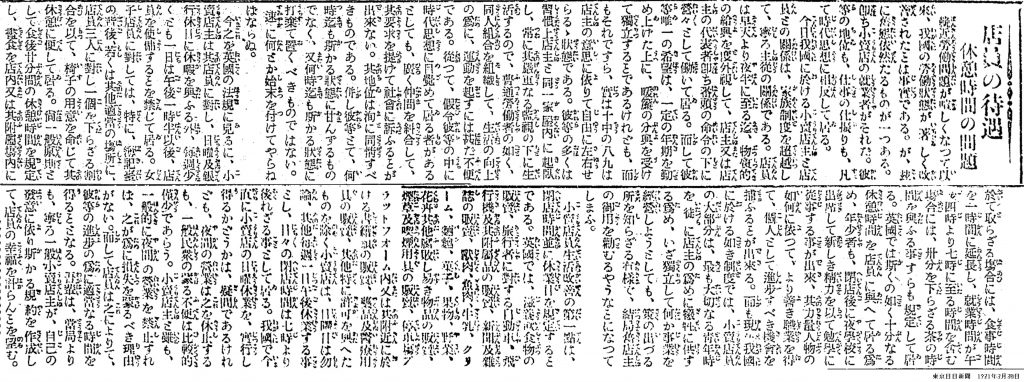

On Wednesday, March 30, 1921, an editorial calling for better treatment of retail employees appeared in the Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun. While the labor movement was gaining momentum in the Taisho era and the treatment of factory workers was improving, the retail industry was still treated poorly as an extension of the old ways of apprenticeship. Many stores did not even have regulations on closing hours and days off, and long working hours were common.

The above is an article from the Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, and it shows that even in the Taisho era, when the labor movement was in full swing, the retail industry was still largely the same as it was in the Edo era. Even today, the retail industry, the real estate industry, and various service industries are still regarded as the “black three industries. Of course, labor laws have been improved and the treatment of workers is much better now, but the structural tendency to work in black industries may not have changed much.

Here, I would like to introduce a description of merchant apprentices in the Taisho era from a 2006 paper by Professor Osamu Saito of Hitotsubashi University.

A merchant’s apprentice is a minor who was under Yeh’s time discipline and was transferred to another merchant’s household (which is actually quite similar to a company organization). Because they did not have their own households and were residents, the logic of the organization worked more directly there than in Yeh. The same was true for the period of teshigai, which did not end with the apprenticeship but lasted up to the mid-thirties. Under such a system, it is no exaggeration to say that the apprentices were controlled at all times. In fact, the female playwright Hasegawa Shigure, who was born in the early Meiji period, called the life of a servant “the life of a shopkeeper’s slave” and wrote the following recollections about the Edo branch of the kimono wholesaler Daimaru. Some years before the earthquake, I saw the windows of the brothel from the back. There was also a wire mesh there. I said it was for fear of the escape of the prostitutes, but it was years before that, in Nihonbashi, in the center of the Imperial Capital, in a place that could be called the center of Japan because of its location in the center of the district, there was a large kimono store with such a window, and a wire mesh covering more than half of the window. I knew this even as a child. They said they were afraid of thieves, but if that was the case, they didn’t have to cover the kitchen windows. I was not afraid of thieves from outside. Whether Hasegawa’s comparison with “prostitutes” and “slaves” is appropriate or not, strict time management was also seen in other large stores. Osamu Saito, “From Peasant’s Time to Company’s Time : Historical Transformation of Labor and Life in Japan,” Journal of Social Policy Studies, 2006, vol. 15.

As mentioned above, from the eyes of a woman like Shigure Hasegawa, who was enjoying the free atmosphere of the Taisho era, it seems that the servants of merchant families were sometimes seen as prisoners trapped in the house.

Leave a Reply