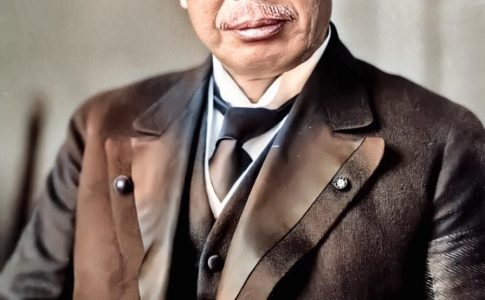

The recent appearance of former Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda in the Nikkei Newspaper’s renowned column “My Resume” raises eyebrows, especially given the controversial timing amidst the ongoing challenges of his “unprecedented monetary easing” policy. This policy, launched over a decade ago and characterized by the mantra “2 years, 2%, 2 times,” has survived numerous amendments but failed to achieve its core goal of 2% inflation. Kuroda’s successor, Kazuo Ueda, is currently grappling with the side effects of this policy, including currency devaluation and increased fiscal risks.

Kuroda’s entry in “My Resume,” a column traditionally reserved for individuals with significant achievements in politics, economics, culture, and sports, seems premature. While he undoubtedly qualifies for his role in Abenomics and implementing a “grand social experiment,” the timing is questionable, especially with Ueda struggling to contain the policy’s side effects.

The article’s title, “Chasing National Interest,” hints at Kuroda’s perspective on his tenure. However, his narrative, sprinkled with grandiose terms like “national interest,” “destiny,” and “trial,” might obscure the need for a balanced and critical evaluation of his policy.

A closer look at the effects of Kuroda’s policy reveals mixed results. While corporate profits nearly doubled and over 4 million jobs were created, the policy’s impact on Japan’s real GDP was modest, with only a 0.5% annual increase. Moreover, while exports, capital investment, and public demand rose significantly, household-related expenditure, such as personal consumption and housing investment, fell below pre-policy levels.

https://facta.co.jp/article/202312005.html

Kuroda’s “grand social experiment” undoubtedly boosted corporate profits, primarily benefiting export industries, but it failed to translate into significant domestic investment or wage growth. This disconnect raises questions about the policy’s ultimate beneficiaries and those who bore its costs.

While Kuroda’s policy cannot be solely blamed for its outcomes, it was a crucial element of Abenomics, which lacked an effective growth strategy and failed to develop a resilient energy strategy in the face of rising import prices. Ueda’s more cautious approach to monetary policy, acknowledging its side effects, contrasts sharply with Kuroda’s defensive stance on criticisms of the policy’s impact on currency devaluation.

In sum, Kuroda’s narrative in “My Resume” should contribute constructively to the ongoing evaluation of this “grand social experiment,” ensuring that lessons learned pave the way for better economic policymaking in the future.

Leave a Reply