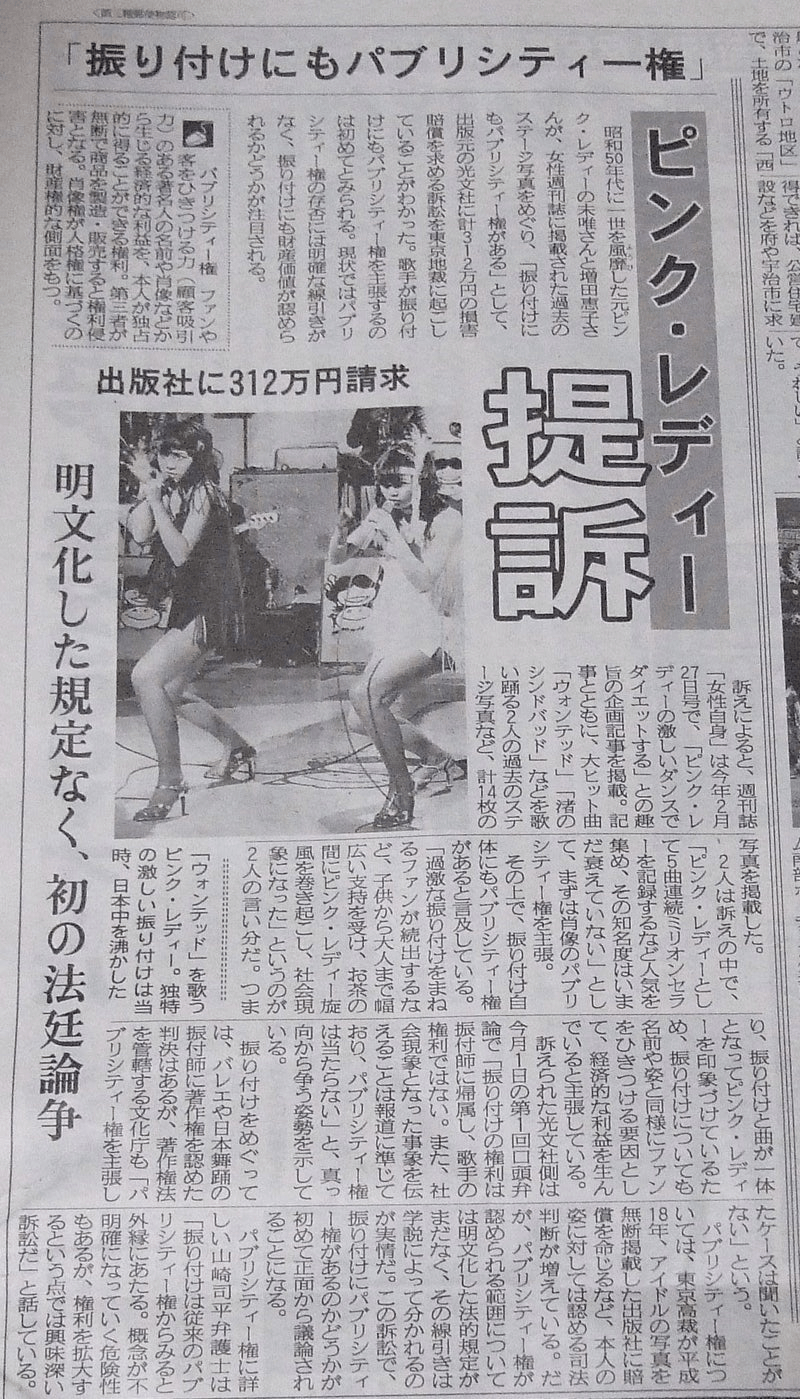

On February 2nd of this year, Japan’s Supreme Court issued a landmark decision regarding the right of publicity, a ruling that drew considerable attention as it was the first time the court had determined the significance and infringement criteria of this right. The case in question, widely covered in the media as the “Pink Lady case,” involved a lawsuit by the members of Pink Lady, a popular music duo, against a publisher for unauthorized use of their photographs in a magazine article titled “Pink Lady de Diet.”

The article in question had featured 14 photographs of Pink Lady, explaining a diet method inspired by the choreography of their songs. The photographs depicted various iconic poses from their performances. The core of the dispute was whether the unauthorized publication of these photographs constituted an infringement of the right of publicity, with Pink Lady seeking approximately 3.7 million yen in damages.

However, the Supreme Court ruled that the unauthorized use of the photographs did not constitute an illegal infringement of the right of publicity, thus rejecting the compensation claim. The court acknowledged that while individuals have a right, derived from their personality rights, not to have their names and likenesses used indiscriminately, the publicity right – the exclusive right to utilize the commercial appeal of one’s name and likeness – is also a part of these personality rights.

The court’s decision stipulated that unauthorized use of an individual’s likeness, even if it possesses customer appeal, could be tolerated as a legitimate form of expression in certain cases. Specifically, illegal infringement of the right of publicity occurs only when the use is predominantly aimed at exploiting the individual’s customer appeal.

This ruling significantly limits the scope of scenarios where unauthorized use of a person’s likeness in commercial activities, such as publishing or broadcasting, could be considered an infringement of the right of publicity. It provides a clearer framework for determining when the use of a person’s image in media and commercial content crosses the line into illegality, emphasizing the need for a distinct and direct commercial exploitation for it to be considered an infringement.

The Pink Lady case thus sets an important precedent for how the right of publicity is interpreted and enforced in Japan, particularly in the context of media and commercial activities, and marks a critical development in the broader discourse on personality rights and commercial expression.

Leave a Reply